The Ecology of Connection

Part 1 of The Anatomy of Empathy

Chronosystem

Human connection has never changed. It is the holy, empty relic of the eternal context in which all creation is lovingly held. Psychologically, it is preverbal and precognitive. Biologically, it is necessary for human life. Ontologically, it is a precondition for time.

Human communities have coalesced and dissolved an uncountable number of times across peoples and eras, but the stories we tell about love have not differed very much. Connection occupies the heights and depths of imagination. Every culture and era reinvents the family labyrinth, the star-crossed lovers, the blood brotherhood, the vengeful, abandoned suitor, the Oedipal tragedy. We are exquisitely sensitive to uncanny representations here, just as with human faces, for the same reasons. We reject stories that are carved too far from love’s mystical joints. We know the forms by heart.

Macrosystem

In the last half century, American culture has undergone a genuine renewal of its narrative about connection and intimacy. Where the moral framework of the previous century was patriarchal, stoic, encased in an icy dignity, the new order is collectivist, medicalized and completely obsessed with power. The new framework - a synthesis of cognitive-behavioral theory and perennially traumatized French postwar criticism - deconstructs traditional concepts and reassembles them in the service of psychotherapeutic individualism. Most of these deconstructions have done little more than to strip common understanding and replace it with mealy-mouthed euphemisms and the foaming cognitive sanitizer of “therapy speak.” But some, such as the feminist redeployment of “vulnerability”, which genders basic honesty as a feminine trait, have contributed to a genuine cultural coup.

Rather than seeking to deeply connect, or to communicate our deepest experiences, we now primarily use language to try and shield our inner world from visibility and social culpability.

Among the American upper and middle classes, who produce most of world culture, this framework has taken its place at the apex ideological niche: it is now an unspoken assumption - plain common sense. The trouble, of course, is that in the absence of traditional social construction, common sense does not reflect social consensus. Social consensus is, indeed, no longer possible, because we do not know to what we are consenting.

We no longer know how to treat one another across contexts. We have to reinvent the wheel for each hookup, each friendship, each business partnership, each new human life brought into the world. Our interactions are fraught and often pathetic. Our attempts to accomplish the psychoanalytic ideal - to make the unconscious conscious - have yielded results any two-bit psychoanalyst could have predicted: We now automatically, unconsciously repress any feelings of genuine human connection, lest they open us to attack.

This means, of course, that we are desperate for connection, even as we disavow it. We crave it, but we can only tolerate it in a form with enough plausible deniability/ironic distance that we can open up a space from it. That is, we want to have it, while being able to keep ourselves perpetually separate from it.

This is precisely the specialty of Western media.

Exosystem

In order for a new story to be observed on a screen, it must first be reified, then harrowed, stripped of nuance and re-caricatured. Once it can be internalized without being understood, and weaponized without giving away the speaker’s position, it is ready to begin.

It first erupts in the group chats and listservs of the coastal literati, then cools as it expands - first to social media influencers, then to the websites of magazines and newspapers, and finally, to talk shows and television. By the time it has been fully processed - let’s say Oprah-fied, with apologies to my younger readers - it is ready to illuminate as many screens as possible.

At this point, it begins to collect its Oort cloud: trillions of icy, hermeneutic little pieces of internet content. Blogs, thinkpieces, GPT-generated listicles, YouTube explainers, TEDx speeches, pseudotherapeutic tweets - each orbits and distorts the surface of the concept while skillfully eliding its depths. In this environment, the universal is impossible to locate within the particular. So it is instead sacrificed.

We have more media than at any point in history, more language than we have ever had to talk about love. Yet, the gulfs between us only grow vaster.

Mesosystem

There has never been any consensus, not in science, religion or anywhere else, when it comes to understanding the intricacies of love. Nobody has a comprehensive system, because it is not a mechanical phenomenon. It defies all attempts at rigorous classification. Everyone knows how it feels but no one can tell you what it is. Depending on who you’re talking to, the terminology of connection - sympathy, compassion, empathy - can all mean sharply different things, or can overlap so much that the distinctions are meaningless. Like all phenomena, love changes shape depending on how closely you observe it.

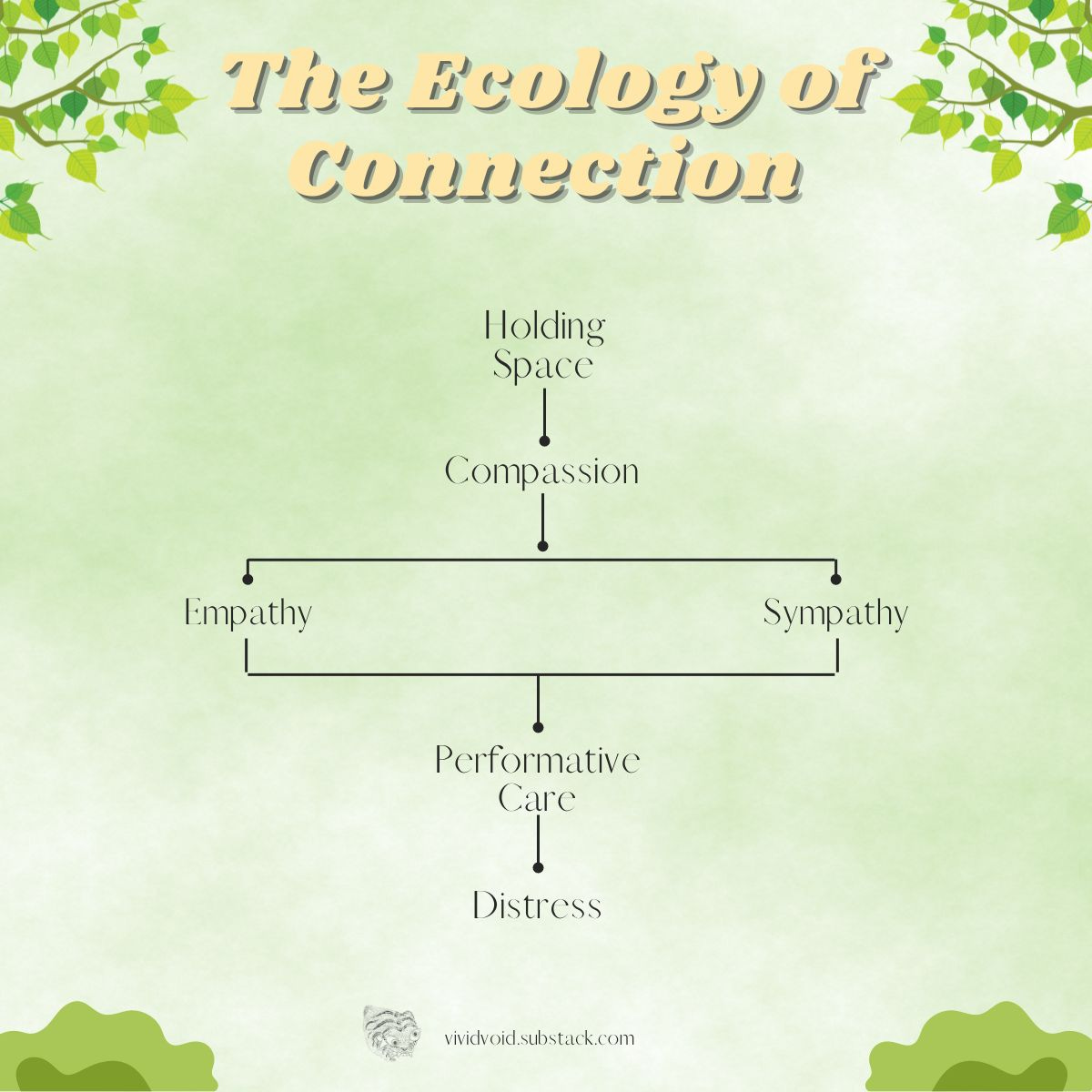

But here in this small series, I ask you to humor me - we have temporary need of a taxonomy, so I will attempt to sketch something for provisional use. I believe we can, for our limited purposes, organize the categories of human sympathetic connection as such, in order of descending Quality:

Holding Space → Compassion → Empathy & Sympathy → Performative Care → Distress.

Or, if you prefer, this handy chart that I would be thrilled if you would help me share on social media:

Let’s begin at the bottom.

When a human being is first born, before it has developed an authentic self strong enough to meaningfully separate from its mother, it can not handle the difficult feelings of another person without experiencing emotional distress. This is a phenomenon known as sympathetic distress, and can also be found in adults with a weak sense of self, and those who are stressed to the point of overwhelm. Both of these signifiers are common in the hollowed-out working class, the addicted and mentally ill, and the terminally burned out. All of that to say, this is how culture and media designate the hopelessly unfashionable.

Most thinkpieces, popular books and TED talks about “vulnerability” and “empathy” are not really concerned with vulnerability or empathy. They are concerned with condemning sympathetic distress, and advising their consumers on how to distance themselves from those who experience it. They are not written for people who already understand these concepts - otherwise, they would require no explanation. Rather, they are written for anxious middle class strivers who need to strategically appear to understand these concepts in front of their professional and bourgeois bosses.

These are the adults most likely to display the second category of relational behavior, performative care. This is a kind of disorganized attachment - too cognitive when it needs to be affective, too affective when it needs to be cognitive. It is the shallow labeling of intersubjective phenomena, a corralling of Being into legible, inclusive forms that everyone can experience with minimal anxiety. It is care without a true or deep emotional connection - an unconscious, enculturated reflex. You may only suffer, acknowledge the suffering of others, and have your suffering cared for, so long as the suffering is pro forma.

“Performative care” is not only too much of a mouthful, it’s far too honest for anyone trapped in a habit of it, so in recent years, it has been Oprah-fied. The word “sympathy,” once understood as the mechanism by which one’s soul is stirred by a leader’s speech, or by which one experiences the fathomless depths of feelings only communicable by great art, has been redefined to mean “insincerity.” The idea of expressing sympathy for another’s loss is now painfully gauche. “Empathy,” on the other hand - ah, it is a new word’s turn to enjoy a glowing pop-psych aureole. Empathy does everything sympathy used to do, and sympathy has been demoted. In our new scheme, sympathy pretends to feel for someone, empathy actually feels with someone. Therefore, empathy is clearly the socially superior response.

Notice: Nowhere in this new folk taxonomy does the term “empathy” carry any of its baggage from its time as a German philosophical concept, nor its years moonlighting as a technical, psychological term of art. Nowhere does Brené Brown hint that empathy and sympathy might once have been separate phenomena for a reason. If she did, we would all need to acknowledge that empathy is connected to fellow-feeling, but is not in fact something that occurs within the domain of affect. Empathy is, in fact, a composite cognitive ability, which when practiced skillfully, engenders accurate feelings of sympathy. It is made up of two parts: the first is the ability to imagine another person’s objective situation and infer their subjective experience. The second is the ability to imagine another person’s subjective experience and infer their objective situation.

In less dense language, empathy is the ability to put yourself in another’s shoes, and the ability to make reasonable conjectures as to why others behave the way they do. It is how we come to understand the interactions between people in relationships, and the interactions between a person’s feelings, their environments and their external conditions. Thus, empathy naturally follows from an ecological perspective of a human being - an intimate understanding of someone as both a responsible agent, free within those physical and social systems that they have thus far mastered, and an inseparable, unconscious function of the systems which they have not.

When empathy is practiced unskillfully, it produces a habit of unwise sympathy that the Buddhists colorfully call “idiot compassion.” It is a well meaning expression of fellow-feeling, but one that ultimately burdens a suffering person, by heaping unneeded judgment, worry and emotion on top of what they are already experiencing.

When empathy is practiced skillfully and with sufficient sympathy, it becomes the ancient religious virtue of compassion - an effortlessly wise, humane response to the suffering of another human being. When someone has great compassion - which is to say, both great sympathy and great empathy, their presence and connection becomes something transcendent.

Microsystem

When we examine human connection at the closest possible level - the level of the individual, situated at the beating heart of their nested ecologies - we see that the Quality of relational behaviors boils down to one fundamental trait: the simple awareness of one’s interconnectedness with all things.

The more an individual is aware of their inseparability, the more vivid and beautiful their connection with others becomes, even entering the heights of mystical experience. And so we come to holding space, the truest individual exercise of compassion. It is the practice of compassion elevated to the level of a healing art, the foundation of psychotherapy, and one of the highest forms of love. To hold space is to erase the false division between the affective and cognitive, the subjective and the objective, the sufferer and the witness.

Like many mystical practices, it is a familiar process: One withdraws the ego, applies close, loving attention, and finally unites that which was once separated. To hold space is, simply, to meditate another’s suffering.

It is intensely difficult, if not impossible, to help someone else heal without a great deal of practice. You can not hold space for another until you have held space for yourself. You can not meditate another’s suffering until you have meditated your own.

This is how you hold space, for yourself or anyone at all: Sit, breathe and listen. Be fully present with the person who is suffering. Do not deny or suppress your sympathetic feelings. Feel the fullness of your emotions, but refrain from expressing or showing them. By staying connected with yourself, stay connected with the sufferer; by withholding your expression, you allow them a complete, uninterrupted experience of their suffering.

Pay close, loving, non-judgmental attention to anything the sufferer expresses, says or does. There will be a time to ascribe responsibility and blame, but not now. Listen intently, understand, be with them, for as long as it takes for them to finish expressing their suffering.

When their experience is complete, when they have emptied themselves of their anguish, they will slowly return to a neutral, restored sense of themselves. Their life will begin to flow again, without resistance. The “I” that was suffering will become an “I” that once suffered. They will find something to laugh about.

And then, they will reconnect to you. This closes your self-imposed separation, the holy wound that you opened in yourself, that you held open, so that they could heal. In that reunion, you are both made whole - you are returned to one another.

You can both love with your whole hearts again.

You won’t be able to help yourself. It’s not up to you.